Lab 6 - Registers and Memory Addressing

Task: Division of Two Numbers

You will solve this exercise starting from the divide.asm file located in the drills/tasks/div/support directory.

In the divide.asm program, the quotient and remainder of two numbers represented as bytes are calculated.

Update the area marked with TODO to perform divisions dividend2 / divisor2 (word-type divisor) and dividend3 / divisor3 (dword-type divisor).

Similar to the mul instruction, the registers where the dividend is placed vary depending on the representation size of the divisor.

The divisor is passed as an argument to the div mnemonic.

TIP: If the divisor is of type

byte(8 bits), the components are arranged as follows:

- the dividend is placed in the

axregister- the argument of the

divinstruction is 8 bits and can be represented by a register or an immediate value- the quotient is placed in

al- the remainder is placed in

ahIf the divisor is of type

word(16 bits), the components are arranged as follows:

- the dividend is arranged in the

dx:axpair, meaning itshighpart is in thedxregister, and thelowpart is inax- the argument of the

divinstruction is 16 bits and can be represented by a register or an immediate value- the quotient is placed in

ax- the remainder is placed in

dxIf the divisor is of type

dword(32 bits), the components are arranged as follows:

- the dividend is arranged in the

edx:eaxpair, meaning itshighpart is in theedxregister, and thelowpart is ineax- the argument of the

divinstruction is 32 bits and can be represented by a register or an immediate value- the quotient is placed in

eax- the remainder is placed in

edxTIP: If the program gives you a

SIGFPE. Arithmetic exception," you most likely forgot to initialize the upper part of the dividend (ah,dx, oredx).

If you're having difficulties solving this exercise, go through this reading material.

Task: Multiplying Two Numbers

1. Multiplying Two Numbers represented as Bytes

You will solve this exercise starting from the multiply.asm file located in the drills/tasks/mul/support directory.

Go through, run, and test the code from the file multiply.asm.

In this program, we multiply two numbers defined as bytes.

To access them, we use a construction like byte [register].

When performing multiplication, the process is as follows, as described here:

- We place the multiplicand in the multiplicand register, meaning:

- if we're operating on a byte (8 bits, one byte), we place the multiplicand in the

alregister; - if we're operating on a word (16 bits, 2 bytes), we place the multiplicand in the

axregister; - if we're operating on a double word (32 bits, 4 bytes), we place the multiplicand in the

eaxregister.

- if we're operating on a byte (8 bits, one byte), we place the multiplicand in the

- The multiplier is passed as an argument to the

mulmnemonic. The multiplier must have the same size as the multiplicand. - The result is placed in two registers (the high part and the low part).

2. Multiplying Two Numbers represented as Words / Double Words

Update the area marked with TODO in the file multiply.asm to allow multiplication of word and dword numbers, namely num1_dw with num2_dw, and num1_dd with num2_dd.

TIP: For multiplying word numbers (16 bits), the components are arranged as follows:

- Place the multiplicand in the

axregister.- The argument of the

mulinstruction, the multiplier (possibly another register), is 16 bits (either a value or a register such asbx,cx,dx).- The result of the multiplication is arranged in the pair

dx:ax, where the high part of the result is in thedxregister, and the low part of the result is in theaxregister.For multiplying

dwordnumbers (32 bits), the components are arranged as follows:

- Place the multiplicand in the

eaxregister.- The argument of the

mulinstruction, the multiplier (possibly another register), is 32 bits (either a value or a register such asebx,ecx,edx).- The result of the multiplication is arranged in the pair

edx:eax, where the high part of the result is in theedxregister, and the low part of the result is in theeaxregister.NOTE: When displaying the result, use the

PRINTF32macro to display the two registers containing the result:

- Registers

dxandaxfor multiplying word numbers.- Registers

edxandeaxfor multiplying dword numbers.

If you're having difficulties solving this exercise, go through this reading material.

Task: Sum of first N natural numbers squared

You will solve this exercise starting from the sum_n.asm file located in the drills/tasks/sum-squared/support directory.

In the sum_n.asm program, the sum of the first num natural numbers is calculated.

Follow the code, observe the constructions and registers specific to working with bytes. Run the code.

IMPORTANT: Proceed to the next step only after you have understood very well what the code does. It will be difficult for you to do the next exercise if you have difficulties understanding the current one.

Start with the program sum_n.asm and create a program sum_n_square.asm that calculates the sum of squares of the first num natural numbers (num <= 100).

TIP: You will use the

eaxandedxregisters for multiplication to compute the squares (using themulinstruction). Therefore, you cannot easily use theeaxregister to store the sum of squares. To retain the sum of squares, you have two options:

- (easier) Use the

ebxregister to store the sum of squares.- (more complex) Before performing operations on the

eaxregister, save its value on the stack (using thepushinstruction), then perform the necessary operations, and finally restore the saved value (using thepopinstruction).NOTE: For verification, the sum of squares of the first 100 natural numbers is

338350.

If you're having difficulties solving this exercise, go through this reading material.

Task: Sum of Elements in an Array

Introduction

You will solve this exercise starting from the sum-array.asm file located in the drills/tasks/sum-array/support directory.

In the sum-array.asm file the sum of elements in an array of bytes (8-bit representation) is calculated.

Follow the code, observe the constructions and registers specific for working with bytes. Run the code.

IMPORTANT: Proceed to the next step only after thoroughly understanding what the code does. It will be difficult for you to complete the following exercises if you have difficulty understanding the current exercise.

Sum of Elements in an Array of types word and dword

In the TODO section of the sum-array.asm file, complete the code to calculate the sum of arrays with elements of type word (16 bits) and dword (32 bits);

namely, the word_array and dword_array.

TIP: When calculating the address of an element in an array, you will use a construction like:

base + size * indexIn the construction above:

- base is the address of the array (i.e.,

word_arrayordword_array)- size is the length of the array element (i.e., 2 for a word array (16 bits, 2 bytes) and 4 for a dword array (32 bits, 4 bytes))

- index is the current index within the array

NOTE: The sum of elements in the three arrays should be:

sum(byte_array): 575sum(word_array): 65799sum(dword_array): 74758117

Sum of Squares of Elements in an Array

Starting from the program in the previous exercise, calculate the sum of squares of elements in an array.

NOTE: You can use the

dword_arrayarray, ensuring that the sum of squares of the contained elements can be represented in 32 bits.NOTE: If you use the construction below (array with 10 elements)

dword_array dd 1392, 12544, 7992, 6992, 7202, 27187, 28789, 17897, 12988, 17992the sum of squares will be 2704560839.

If you're having difficulties solving this exercise, go through this reading material.

Task: Count Array Elements

Count Negative and Positive Numbers from Array

You will solve this exercise starting from the count_pos_neg.asm file located in the drills/tasks/vec-count-if/support directory.

Your program should display the number of positive and negative values from the array.

NOTE: Define a vector that contains both negative and positive numbers.

TIP: Use the

cmpinstruction and conditional jump mnemonics. See details here.TIP: The

incinstruction followed by a register increments the value stored in that register.

Count Odd and Even Numbers from Array

Create a new file called count_even_odd.asm file located in the drills/tasks/vec-count-if/support directory.

Your program should display the number of even and odd values from an array.

TIP: You can use the

divinstruction to divide a number by 2 and then compare the remainder of the division with 0.NOTE: For testing, use an array containing only positive numbers.

For negative numbers, sign extension should be performed; it would work without it because we are only interested in the remainder, but let's be rigorous :-)

If you're having difficulties solving this exercise, go through this reading material.

Registers

Registers are the primary "tools" used to write programs in assembly language. They are like variables built into the processor. Using registers instead of direct memory addressing makes developing and reading assembly-written programs faster and easier. The only disadvantage of programming in x86 assembly language is that there are few registers.

Modern x86 processors have 8 general-purpose registers whose size is 32 bits.

The names of the registers are of historical nature (for example: eax was called the accumulator register because it is used by a series of arithmetic instructions, such as idiv).

While most registers have lost their special purpose, becoming "general purpose" in the modern ISA (eax, ebx, ecx, edx, esi, edi), by convention, 2 have retained their initial purpose: esp (stack pointer) and ebp (base pointer).

Register Subsections

In certain cases, we want to manipulate values that are represented in less than 4 bytes (for example, working with character strings).

For these situations, x86 processors offer us the possibility to work with subsections of 1 and 2 bytes of the eax, ebx, ecx, edx registers.

The image below represents the registers, their subsections, and their sizes.

WARNING: Subsections are part of registers, which means that if we modify a register, we implicitly modify the value of the subsection.

NOTE: Subsections are used in the same way as registers, only the size of the retained value is different.

NOTE: Besides the basic registers, there are also six segment registers corresponding to certain areas as seen in the image:

Static Memory Region Declarations

Static memory declarations (analogous to declaring global variables) in the x86 world are made through special assembly directives.

These declarations are made in the data section (the .data region).

Names can be attached to the declared memory portions through a label to easily reference them later in the program. Follow the example below:

.DATA

var `db` 64 ; Declares a byte containing the value 64. Labels

; the memory location as "var".

var2 `db` ? ; Declares an uninitialized byte labeled "var2".

`db` 10 ; Declares an unlabeled byte, initialized with 10. This

; byte will be placed at the address (var2 + 1).

X `dw` ? ; Declares an uninitialized word (2 bytes), labeled "X".

Y `dd` 3000 ; Declares a double word (4 bytes) labeled "Y",

; initialized with the value 3000.

Z `dd` 1,2,3 ; Declares 3 double words (each 4 bytes)

; starting from address "Z" and initialized with 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

; For example, 3 will be placed at the address (Z + 8).

NOTE: DB, DW, DD are directives used to specify the size of the portion:

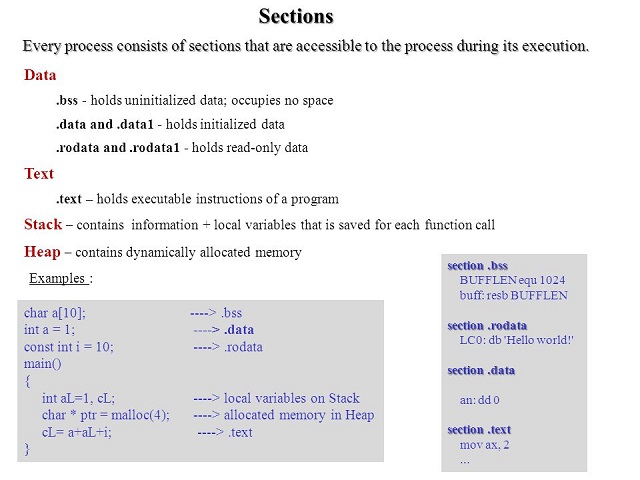

Directive Role Size dbDefine Byte 1 bytes (8 bits) dwDefine Word 2 bytes (16 bits) ddDefine Double Word 4 bytes (32 bits) NOTE: There are multiple types of memory regions as can be seen in the image below:

The last declaration in the above example represents the declaration of an array. Unlike higher-level languages, where arrays can have multiple dimensions and their elements are accessed by indices, in assembly language, arrays are represented as a number of cells located in a contiguous area of memory.

Guide: Multiply and Divide

To follow this guide, you'll need to use the multiply-divide.asm file located in the guides/multiply-divide/support directory.

The program performs the mul and div instructions and prints out the results.

Note: For a detailed description of the instruction check out the following pages: div and mul

Guide: Floating Point Exception

To follow this guide, you'll need to use the floating_point_exception.asm file located in the guides/floating-point-exception/support directory.

The program tries to perform division using an 8 bit operand, bl, in this case the quotient should be in the range [0, 255].

Given that ax is 22891 and bl is 2, the result of the division would be out of the defined range.

Thus we will see a Floating point exception after the division.

Note: For a detailed description of the

divinstruction check out the documentation.

Memory Addressing

Modern x86 processors can address up to 2^32 bytes of memory, which means memory addresses are represented on 32 bits. To address memory, the processor uses addresses (implicitly, each label is translated into a corresponding memory address). Besides labels, there are other forms of addressing memory:

mov eax, [0xcafebab3] ; direct (displacement)

mov eax, [esi] ; indirect (base)

mov eax, [ebp-8] ; based (base + displacement)

mov eax, [ebx*4 + 0xdeadbeef] ; indexed (index * scale + displacement)

mov eax, [edx + ebx + 12] ; based and indexed without scale (base + index + displacement)

mov eax, [edx + ebx*4 + 42] ; based and indexed with scale (base + index * scale + displacement)

WARNING: The following addressing modes are invalid:

mov eax, [ebx-ecx] ; Registers can only be added

mov [eax+esi+edi], ebx ; The address calculation can involve at most 2 registers

Size Directives

Generally, the size of a value brought from memory can be inferred from the instruction code used. For example, in the above addressing modes, the size of the values could be inferred from the size of the destination register, but in some cases, this is not so obvious. Let's consider the following instruction:

mov [ebx], 2

As seen, it intends to store the value 2 at the address contained in the ebx register.

The size of the register is 4 bytes.

The value 2 can be represented on both 1 and 4 bytes.

In this case, since both interpretations are valid, the processor needs additional information on how to treat this value.

This can be done through size directives:

mov byte [ebx], 2 ; Move the value 2 into the byte at the address contained in ebx.

mov word [ebx], 2 ; Move the entire 2 represented in 16 bits into the 2 bytes

; starting from the address contained in ebx.

mov dword [ebx], 2 ; Move the entire 2 represented in 32 bits into the 4 bytes

; starting from the address contained in ebx.

Loop Instruction

The loop instruction is used for loops with a predetermined number of iterations, loaded into the ecx register.

Its syntax is as follows:

mov ecx, 10 ; Initialize ecx with the number of iterations

label:

; loop content

loop label

At each iteration, the ecx register is decremented, and if it's not equal to 0, the execution jumps to the specified label.

There are other forms of the instruction that additionally check the ZF flag:

| Mnemonic | Description |

|---|---|

loope/loopz label | Decrement ecx, jump to label if ecx != 0 and ZF == 1 |

loopne/loopnz label | Decrement ecx, jump to label if ecx != 0 and ZF != 1 |

NOTE: When using jumps in an assembly language program, it's important to consider the difference between a

short jump(near jump) and along jump(far jump).

Type and example Size and significance Description Short Jump (loop) 2 bytes (one byte for the opcode and one for the address) The relative address of the instruction to which the jump is intended must not be more than 128 bytes away from the current instruction address. Long Jump (jmp) 3 bytes (one byte for the opcode and two for the address) The relative address of the instruction to which the jump is intended must not be more than 32768 bytes away from the current instruction address.

Guide: Addressing Arrays

To follow this guide, you'll need to use the addressing_arrays.asm file located in the guides/addressing-arrays/support directory.

The program increments the values of an array of 10 integers by 1 and iterates through the array before and after to show the changes.

Note:

ecxis used as the loop counter. Since the array containsdwords(4 bytes), the loop counter is multiplied by 4 to get the address of the next element in the array.

Guide: Declarations

To follow this guide, you'll need to use the declarations.asm file located in the guides/declarations/support directory.

The program declares multiple variables of different sizes in the .bss and .data sections.

Note: When defining strings, make sure to add a zero byte at the end, in order to mark the end of the string.

decimal_point db ".",0

For a complete set of the pseudo-instruction check out the nasm documentation.

Guide: Loop

To follow this guide, you'll need to use the loop.asm file located in the guides/loop/support directory.

This program illustrates how to use the loop instruction, as well as how to index an array of dwords.

Note: The

loopinstruction jumps to the given label when thecountregister is not equal to 0. In the case ofx86thecountregister isecx.Note: For a detailed description of the

loopinstruction check out the documentation.